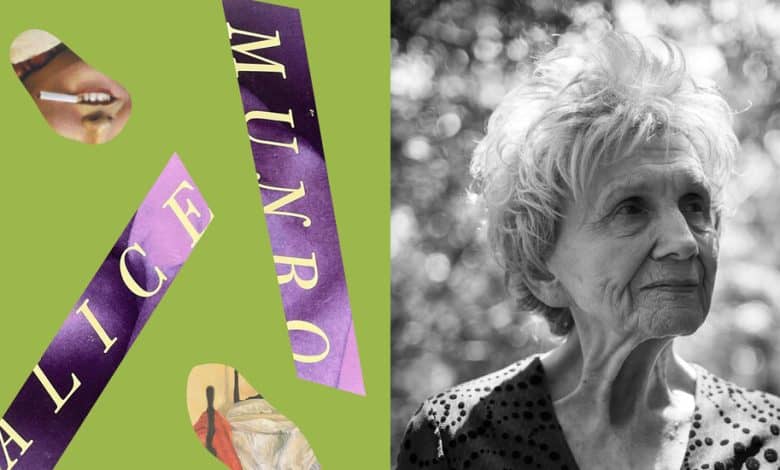

The Essential Alice Munro

Before I’d read Alice Munro — when my knowledge of her amounted to an oafish word cloud (“older woman,” “Canadian,” “short stories”) — I imagined that the experience of reading her books, if I ever bothered to, would be like listening to classical music on fancy headphones in a college library: civilized, subtle, probably sleep-inducing.

But then I actually read Munro, and she lifted off my headphones in order to whisper an insane, unforgettable piece of gossip about that anxiety-stricken T.A. over by the copy machine. It turns out that Alice Munro — Nobel laureate, Author Most Likely to Endure, object of universal writerly reverence and envy — is not just important, but fun. Her books don’t belong on a high shelf; they belong in the passenger seat of your car, in the tote bag you bring to the grocery store. She writes about penises that look “blunt and stupid, compared, say, to fingers and toes with their intelligent expressiveness”; old people who smell like rank flower water; the way that couples breaking up occasionally interrupt the solemn proceedings to have passionate sex.

The prerequisites for appreciating Vladimir Nabokov, for example, include an appreciation for cryptography, a rudimentary knowledge of chess and a passing familiarity with Pushkin. The prerequisites for reading Munro are: having lived.

Before her retirement in 2013, she wrote 14 short story collections (a couple of which may try to pass themselves off as novels — don’t believe them). Almost all her stories take place in rural Ontario and follow the general contours of her life: the childhood on a struggling farm; the chronically ill mother; the early, unsuccessful marriage; the romantic escapades and agonies.

This fixity of focus, this tendency to return, like a patient in psychoanalysis, to the same cluster of significant autobiographical incidents, has led some critics (perhaps with a dab behind the ears of eau du sexism) to treat her as a minor talent. Enough with the intelligent, anguished heroines waiting at rural train stations! Give us Bellow with his lion-hunting Henderson, Mailer with his century-swallowing fever dreams!

This is stupid for lots of reasons, but one of them gets at a quality of Munro’s that is hugely important but hard to articulate. Her writing, once ingested, lives on in a different part of the brain than that of most writers. After 20 years of reading her and raving about her to anyone within earshot, I can recite hardly a single sentence. But I remember moments from her books (Lottar wrapped in the lice-infested rug; Del walking drunk along the edge of the grass) more vividly than I remember entire years of my life. She goes out of her way not to be a phrasemaker; much of her writing has the murmury, urgent, working-it-out-in-real-time quality of someone writing by hand on a bouncy bus. She makes memories instead.